Most of the time, I feel ambivalent about being a psychologist. I feel uncomfortable and tense in my role of ‘advice giver’ since I don’t believe that giving advice is so helpful anymore. That’s because in the world of self-help advice - is that an oxymoron? - we’re in a moment of superabundance. And I don’t mean in a good way.

I touched on this in my last post about how the parenting advice industry - Big Parenting, if you will - has placed more pressure on parents rather than alleviating it. It makes us parents feel like parenting - and childhood - is just one huge problem to solve. It boils down to this:

As the classic communication theory concept of Marshall McLuhan goes, the medium is the message. And the key media for parenting advice, social media, convey some messages with crystal clarity: Parenting is a never-ending checklist of do’s and don’ts; we should access outside expertise on a daily basis; and our dream of being good parents might be just a TikTok or New York Times bestseller away.

I don’t want to call out any particular parenting experts. As I said, I believe the intentions here are largely benign - even when packaged in daily barrages of Instagram posts and sleek corporate marketing. But their ubiquity and their tone, which ranges from solicitous concern to abject alarm, tell us something different. They tell us parents to remain vigilant. They warn us against falling asleep at the wheel on this long-haul, cross-country drive called parenting. They end up convincing us to trust ourselves less, judge ourselves more harshly, and to keep coming back for more advice. This is a recipe for intensive parenting.

This isn’t just a problem with parenting Influencers. It’s a problem with the whole self-help industry. It was always inching towards this, but has reached a stress and pressure apotheosis because now, the industry is engineered for the sole purpose of convincing us that It’s Never Enough.

Rates of Return

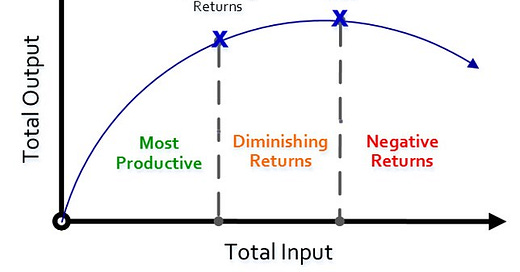

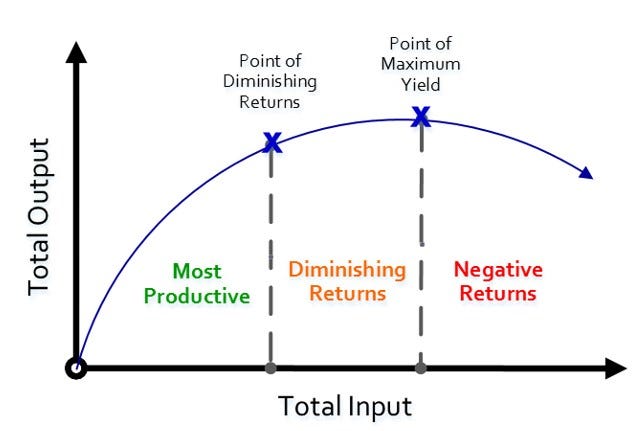

A rate-of-return analogy shows us how1.

Consider human effort. Most of us assume that hard work pays off, and, conversely, that if a task should take a day, and we only devote an hour to it, results won’t be up to snuff. Research consistently backs up this intuition – when students invest more time, effort, and energy to studying, their grades go up. When people face difficult goals, they generally outperform those with easy goals because they put in the extra effort and personal investment. As the input of time and energy increases, the output of success and performance proportionally rises, too. This is the zone of increasing returns – one unit of work pays off in one unit of improvement. Simple math.

The math, however, isn’t quite that simple, because it turns out that it’s not just quantity that matters. Quality does too. The more purposeful we are in our efforts, and the more clear and attainable our goals, the better our performance and learning. Simple quantity of effort can backfire. And when it does, we hit the point of diminishing returns – efficiency is out the window and putting in more time and effort yields smaller and smaller improvements. in other words, at a certain point adding more effort will not produce significantly more gains.

Worse yet, diminishing returns can escalate into negative returns, where putting in more time and effort actually makes things worse. It’s like adding extra hours of training at the gym, on top of the recommended regimen, only to realize that you’ve over-trained and are so depleted that you can’t even do the basics anymore. Or continuing to tweeze your eyebrows in pursuit of that perfectly shaped arch until your brow has all but disappeared – and you have to draw it in with a pencil, like your grandmother.

That’s where the self-help advice industry tends to land us - in the zones of diminishing and negative returns, where putting in more effort to achieve that elusive feeling that ‘I’m ok’ just makes us less happy and less well. And with tiny eyebrows.

Any of our efforts can fall into these zones of increasing, diminishing, and negative returns. Imagine two people who have been feeling overwhelmed and decide to try meditation. One person is on the self-help advice treadmill and the other isn’t. In which zone will each land? They both have to figure out what kind of meditation to try, how much time to spend doing it, how to create a routine, etc,…

People sprinting on the treadmill are prone to finding themselves in the zone of diminishing returns. They’re putting in effort, but they can become unfocused or distracted by the endless options and social comparisons. They might spend hours scrolling through meditation-adjacent ads in their social media feeds (instead of meditating), or convinced by a new Influencer every week that this hot new meditation technique is the one. So, they delay committing and get caught up half-heartedly ‘doing research,’ putting in the time but essentially spinning their wheels. It’s paralysis by analysis.

Someone off the treadmill, in contrast, is less prone to these distractions. It’s not easy, but they start putting in a reasonable amount of effort and do it in targeted and strategic ways, like talking to a friend who meditates or identifying one meditation center or acclaimed book to start with. They just do it, unburdened by what the world of experts tells them, or waiting to be inspired by the star of their favorite tv show whose life was transformed by meditation. They put in the work, and soon, they find that the quality of their meditation routine proportionally improves with each hour they spend. They’re in the zone of increasing returns.

As time passes for each of our meditators, you see even more differences emerge. People sprinting on the treadmill can get stuck on the surface rather than going deeper. They’re tracking what others think of meditation more than checking their own gut. This is especially the case if the meditator seeks information on social media. Meditation tips are de-contextualized into pieces of content, information bits to be consumed, bought, and sold. The imperative of wellness social media is not to convey wisdom or to heal, but to advertise and engineer content so that it pleases the algorithm and is served up to the most people the most times.

Someone on the treadmill might make more choices based on likes and followers of the advice givers or number of books sold instead of what makes the most sense to them and will fit into their lives. The distractions and self-doubts keeps them running after Always More. There, they fall into the zone of negative returns, where each hour of time seems to be backfiring, with peace of mind feeling further away than ever.

When we step off the wheel, it’s easier to titrate our efforts and go for that sweet spot between the perfect and the merely ok meditation practice. Without the constant need to learn more, do more, and compare ourselves more to all the perfect meditators out there, we can actually spend our time investing sufficient – but not excessive - effort to reach an attainable goal.

Life isn’t A Problem to Solve

“Is there really anything we can do about this?,” you might be wondering, or, perhaps more pointedly, “Aren’t YOU, Tracy, a part of the advice treadmill problem?”

Good questions, and the answer to both of them is yes.

I think we can do something about this, and I’m particularly committed to figuring out how because, yes indeed, I am a part of the problem. Even by writing this, I’m adding to the noise and the constant drum beat of figure it out, more and better, figure it out, more and better, rum-ta-tum, rum-ta-tum….

The key is to step off the treadmill of advice and do less so you can move more towards the zone of increasing returns:

When someone asks me what book they should read when they have a parenting dilemma, I tell them, “Don’t read any of them. What do your instincts tell you? Have you talked to your mom, or uncle, or the wisest person you know? If after that, you still feel you need some input, then we’ll talk and I’ll send you some links.”

I have the impulse even now to make you a list of ways to enter the zone of increasing returns. But I won’t because it’s too risky - it literally puts us right back on the treadmill. And let’s not forget, it’s both simpler and harder than that.

It starts with just deciding to say no to those things that take you away from the zone of increasing returns. They are the very same things that tend to take you away from what’s really real to you: What really matters to you. What really gives you energy. What really allows you to give back to others. The list goes on.

This isn’t advice. This isn’t a problem to solve. This is stuff you already know.

So, since you already know, ask yourself this question: If I didn’t treat life like a problem to solve, what’s the very next thing I’d do?

Note that I don’t want to suggest you should apply economic formulae to building a meditations practice, like R = [ ( Ve – Vb ) / Vb ] x 100, where, R = Rate of return; Ve = End of period value; and Vb = Beginning of period value. This type of thinking is over-simplistic even for accounting, where the time value of money or cash flows should be factored in. Suffice it to say, we should think of the goal here as developing a ‘spinning your wheels’ radar and ‘just get on with it’ default.