A.D.H.D.: Are We Victims of Our Own Medicine?

The Medicalization mindset and an argument for Slow Mental Healthcare

Rick1 always sat in the back row of my Child Psychopathology class. A big guy with dark hair and glasses, he rarely spoke and seemed to alternate between shyness and boredom - until, that is, I began my lecture on A.D.H.D.

Describing the three diagnostic subtypes of the disorder, I asked, “If one person diagnosed with A.D.H.D. can look so different from another person diagnosed with A.D.H.D., is it a true disorder?”

Rick’s hand shot up. “Absolutely,” he said. “Neurodiverse people can have A.D.H.D. in really different ways because everyone’s brain is unique.” This sparked off a passionate debate, featuring several students, like Rick, who self-identified as having A.D.H.D.

I was hopeful that this was the ice breaker Rick needed to become an active member of the class. Unfortunately, I never saw that side of him again. By the time he came to my office hours a few weeks later, he’d missed two important homework assignments, had several absences, and had barely made a C on the midterm. He was in danger of failing.

As we talked about how he could get back on track, he confided that he’d recently, at age 19, been diagnosed with A.D.H.D.

“Things finally made sense,” he said. “My whole life, I felt like I was one step behind everyone else - I was bored and distracted in class, my grades were meh, and I never found “my thing” ….except video games. I’m really good at those. But once I realized I was neurodiverse, I learned that my brain isn’t broken - it’s just different. I spend more time with people like me, and it really helps me cope.”

His doctor started him on Adderall, which helped immediately. He felt more focused and motivated for studying. But while his mind seemed sharper, his mood worsened. He started suffering bouts of depression and anxiety.

“I missed those two homework assignments because I just couldn’t get out of bed.”

We looped in the accommodations office and made a plan for the remainder of the semester, but things didn’t get much better. In the end, he received a final grade that didn’t, I thought, reflect his ability.

A Rising Tide

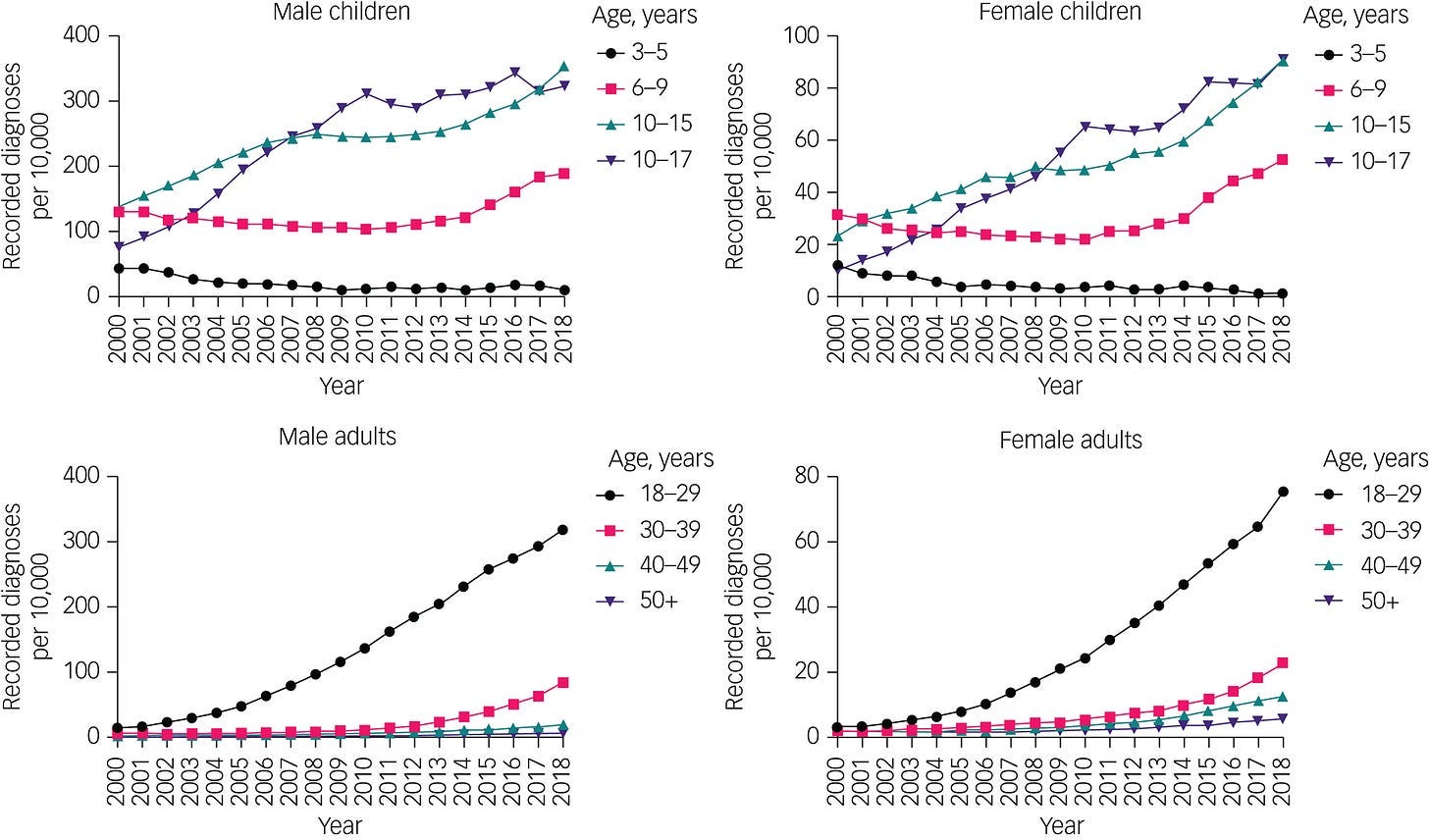

Just a couple decades ago, Rick, as a young adult, might never have received a diagnosis of A.D.H.D. Since 2000, however, the story has changed. Data from the CDC and World Health Organization show that A.D.H.D. diagnoses have risen sharply: childhood diagnoses in the U.S. have gone from 6% to 10%, rates in the U.K. have doubled, and Germany has seen a 77% increase in their relatively low rates, from 2.2% to 3.8%. Yet, the largest proportional increases have occurred among adults like Rick. You can see typical upward trends in data from a large-scale study of diagnoses and prescriptions in UK primary care between 2000-2018.

Fig. 4 Time trends of the proportions of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnoses in children and adults, by gender and age group. From McKechnie et al., 2023

It turns out that these increases are largely due to the diagnosis of more mild cases of A.D.H.D. - which involve fewer and less enduring symptoms, less severe impairment, and less evidence for childhood onset. In other words, there has been diagnostic expansion with more mild to moderate symptoms included under the A.D.H.D. umbrella.

Many professionals, patients, and advocates celebrate these trends, reasoning that more diagnoses mean that more people are being identified and helped - like my student Rick. Others worry that the expansion of diagnostic boundaries might inadvertently pathologize normal personality differences. Could we be doing unknown harm by labelling and medicating healthy people?

In the case of Rick, I could see both sides. The diagnosis helped him make sense of his past struggles, boosted his self-acceptance, and plugged him into a supportive community. Yet, other aspects of his life were the same or worse. He was suffering more from emotional distress, and his grades weren’t improving yet. Maybe the A.D.H.D. diagnosis wasn’t the right fit.

In his feature for the New York Times Magazine, Have We Been Thinking About A.D.H.D. All Wrong?, the journalist

wrestles with these questions. As a father of two teen boys, he’d witnessed the rising tide of A.D.H.D. and prescription stimulant medications in his own community. A.D.H.D. and these drugs suddenly “seemed to be everywhere.”But while the label of A.D.H.D. could explain many of the problems people around him were having, its boundaries were porous. He couldn’t tell where the cutoff was between normal distractibility or fidgeting and clinical inattention or hyperactivity. Health professionals and researchers he spoke to seemed to struggle with the same uncertainty. Although the bar for diagnosing A.D.H.D. had been systematically lowered - with the intent of helping more people - the increased detection hadn’t translated into better outcomes, like lower rates of the disorder over time or higher rates of remission. Tough also found in his reporting that researchers had failed to identify clear biological causes of A.D.H.D. - even after decades of trying. In other words, there are no “biomarkers,” or litmus tests indicating that “you have A.D.H.D. or you don’t.”

Perhaps the issue that concerned Tough the most had to do with stimulant medications like Ritalin and Adderall. Prescriptions for these drugs have skyrocketed over the past decade - increasing in the U.S. by 58 percent overall and tripling among people in their 30’s, from 5 million to 18 million. The research and experts, however, seemed to be saying that these medications weren’t the magic bullet solution people once thought they were.

Tough was troubled, “That ever-expanding mountain of pills rests on certain assumptions: that A.D.H.D. is a medical disorder that demands a medical solution; that it is caused by inherent deficits in children’s brains; and that the medications we give them repair those deficits. Scientists who study A.D.H.D. are now challenging each one of those assumptions — and uncovering new evidence for the role of a child’s environment in the progression of his symptoms.”

Experts like Russell Barkley pushed back hard on Tough’s article, arguing that he’d underestimated the benefits and over-estimated the problems of current treatments. Higher rates of A.D.H.D diagnosis and stimulant medication prescriptions? That’s a success story, Barkley asserted, because medication works - not perfectly, but it has a huge positive impact. And after all, just four or five decades ago, when these drugs and non-drug treatments weren’t readily available, millions of people floundered without support due to rampant under-diagnosis, low treatment accessibility, and stigma.

(For those who want a deep-dive into the debate, watch Russ Barkley respond to Tough’s article point-by-point in his 4-part YouTube video).

Black Holes and Revelations

I soon realized that there was a fundamental problem with this debate. It was caught in the inescapable gravity of a powerful dichotomy: A.D.H.D. is either a “true medical disorder” or we’re “pathologizing normal.”

This is a classic false dichotomy, providing two extreme options as if they were the only choices available.

It’s a dichotomy that permeates the public discourse about A.D.H.D. You see it on social media, where A.D.H.D. denialism and conspiracy theories have taken on epic proportions. You see it in communities where parents of children with A.D.H.D. believe they must decide between medicating forever or rejecting medication altogether. You see it in the notion that you either use medication to repair “inherent deficits in children’s brains” or you address the “role of the child’s environment.”

We remain caught in a debate over extreme and unhelpful positions because of one overarching reality - the Medicalization of mental health

Medicalization

Medicalization is a mindset, a set of principles that guide how we understand and respond to illness. Its core principles are diagnosing and biologizing sickness in order to eradicate it.

Diagnosis is pattern recognition - when an individual’s cluster of symptoms cross a threshold of similarity with a cluster of symptoms that define a disease, you diagnose. The diagnosis then acts as a bridge: connecting what we know about biological causes and defects driving the disease with treatments that eliminate these causes and defects so that the body can work normally again.

Medicalization taught us that chronic exhaustion plus blood iron deficiency should be diagnosed as anemia. Anemia can be remediated by taking supplements to repair this deficit - replenishing iron levels. Et voilà! Problem solved!

Mental healthcare has attempted to apply this same elegant logic to mental illness. When our psychological symptoms match the symptoms that define a mental disease, you diagnosis. This diagnosis connects what we know about the causes and defects driving the dysfunctional thinking, feeling, or behaving with treatments that eliminate these causes and defects so that the person can think, feel, and behave normally again.

For a long time, the logic of Medicalization seemed so reasonable as to represent mere common sense. It was exciting, too, because it promised to yield a cornucopia of new and better treatments, powered by science and accelerated by shiny new technologies.

Yet, Medicalization is a deeply flawed framework for mental healthcare. We see this clearly in A.D.H.D. It fails to neatly conform to the diagnosing and biologizing ideals of Medicalization. As a result, we are pushed into distracting debates about false dichotomies - like whether A.D.H.D. is a “true disease” or not.

Meanwhile, the treatment of A.D.H.D. under this framework has not noticeably changed or improved for a couple decades. Rates of A.D.H.D. continue to rise, as do rates of other mental illnesses like anxiety and depression. In his 2022 book, “Healing,” Dr. Tom Insel lamented that in the 13 years he ran the National Institute of Mental Health, “Nothing my colleagues and I were doing addressed the ever-increasing urgency or magnitude of the suffering millions of Americans were living through — and dying from.”

I believe a fundamental part of the problem is that we’re stuck trying to shove the square peg of mental illness into the round hole of Medicalization - and the benefits no longer seem to quite outweigh the costs.

To get unstuck, we have to see how Medicalization drives false dichotomies that confuse, distract, and generally muddy the waters in how we understand and treat A.D.H.D.

False Dichotomy #1: A.D.H.D. has clear diagnostic cutoffs or it’s not a disorder.

From the perspective of Medicalization, disorders should have clear diagnostic cutoffs. This is already easier said than done for physical illnesses. For mental illnesses, it’s a profound challenge because of their high phenotypic variability - they manifest in different ways for different people.

A.D.H.D. exemplifies phenotypic variability because of its subtypes and high rates of comorbidity. There are three diagnostic subtypes in A.D.H.D.: Predominantly Inattentive, Predominantly Hyperactive/Impulsive, or Combined. A child with the Predominantly Inattentive subtype will likely have difficulty listening and sustaining attention, will often lose, forget, or misplace things, and will probably have significant trouble following directions or getting homework done. A child with the Predominantly Hyperactive/Impulsive subtype, on the other hand, might constantly squirm and fidget, appear “driven by a motor,” and rarely play or sit quietly in school. A.D.H.D. is also highly comorbid, co-occurring more often than not with anxiety disorders, depression, learning disabilities, and oppositional defiant disorder (O.D.D.). Someone diagnosed with A.D.H.D. and depression might show symptoms that are very different than someone with A.D.H.D. and O.D.D.

The diagnostic expansion of A.D.H.D. has further increased phenotypic variability. When the number and severity of symptoms a person must have to receive the diagnosis are reduced, more mild and edge cases are included. While the benefits of this “diagnostic creep” are real - a major benefit is that it allows more access to treatment - it also has potential down-sides. It blurs the boundary, or “cutting point,” between disorder and non-disorder, placing A.D.H.D. on a broad spectrum. The spectrum approach is more inclusive, but risks characterizing people with normal struggles as “sick.” These folks might end up with treatments that are a much better fit for those with more severe symptoms.

Such diagnostic tension, however, is valuable in mental healthcare. It forces us to contend with human variety and edge cases, and to question whether a treatment meets a person’s needs. Unfortunately, when we’re under the sway of Medicalization, we rush too quickly to shut down this tension and uncertainty in favor of adhering to pristine categories - sick or well. Squeezing patients into these categories, even when they don’t fit, degrades the quality of treatment and block us from asking hard questions. For example, if the prevalence of A.D.H.D. in 17-year-old boys in the U.S. is so high - it’s 23% - that it’s almost common, do all these boys really have a disorder?

From the perspective of Medicalization, disorders should have clear diagnostic cutoffs. This is already easier said than done for physical illnesses. For mental illnesses, it’s a particularly poor fit because psychological disorders commonly have high phenotypic variability - they appear in different ways for different people.

Yet, to suggest that researchers like Russell Barkley seek to “...portray A.D.H.D. as a distinct, unique biological disorder” reflects a misunderstanding. It’s Medicalization talking, not the reality of psychological research or practice. Anyone who is even remotely knowledgeable about A.D.H.D. knows that it’s not that simple. As a field, we have long struggled with questions like Tough’s, “Is a patient with six symptoms really that different from one with five? If a child who experienced early trauma now can’t sit still or stay organized, should she be treated for A.D.H.D.? What about a child with an anxiety disorder who is constantly distracted by her worries? Does she have A.D.H.D., or just A.D.H.D.-like symptoms caused by her anxiety?”

Clinical psychologists give diagnoses because we feel we have to - to get insurance to cover treatment, to make sense of how to help a complex human being in front of us. And we try to find ways out of the Medicalization trap all the time. To diagnose A.D.H.D., there has to be functional impairment - life struggles in multiple domains - and lots of disruptive symptoms. This means that suffering and difficulty can be considered “normal” as long as it’s not derailing your life. A diagnosis must further specify whether symptoms are mild, moderate, or severe, to characterize where you fall on the spectrum. These steps are meant to inform and personalize treatment.

Of course, the road to hell can be paved with good intentions. Diagnoses don’t always help - and can do harm, as I’ll describe below. But the biggest problem perhaps is what comes next. Here Medicalization has sent us down a confusing path again - especially when it comes to medication.

False Dichotomy #2: A.D.H.D. can be successfully medicated or it’s not a disorder and shouldn’t be medicated.

Stimulant prescriptions for teens have risen 60% in the past decade. Is that because they “fix” biological defects underlying A.D.H.D.?

Absolutely not. This is a Medicalization red herring. Stimulant drugs like Ritalin or Adderall temporarily improve focus and inhibitory control when they are active. They do nothing to “heal” underlying causes of inattention or hyperactivity, and they stop helping once they’re out of a person’s system.

In other words, stimulants manage symptoms but don’t fix anything, let alone the “A.D.H.D. brain.”

And let’s be clear: This is exactly the case for all psychotropic medications - those for anxiety, depression, psychosis, and beyond. These drugs manage symptoms but don’t heal the illness. They should always be used cautiously because they can lead to paradoxical worsening of symptoms over time. Of course, this caution seems very absent in our pill-popping culture. We should push back against those who treat drugs as a cure-all or who prescribe them lightly.

But that doesn't mean that medication is all bad. Decades of research show that the optimal treatment for promoting long term gains in A.D.H.D. is combining medication with cognitive behavioral and family-focused therapies. This makes sense - medications allow symptoms to be brought under control so that people can benefit more from other therapies. These therapies take effort and time, but can lead to lasting improvements in key engines of resilience - coping and self-regulation skills, relational problem solving, and accommodations at home and in school environments.

Medication is giving a person a fish. They’ll eat for the day. Therapy is teaching a person to fish, giving them a real shot at changing their life - eating for a lifetime, to stick with the biblical metaphor.

Yet, a terrible result of Medicalization is that - despite knowing better - mental healthcare hyper focuses on managing symptoms, and pays short shrift to addressing causal factors - whether biological, psychological, or social. We have no drugs that eradicate mental illness, but we keep acting as if we do.

If we treated cardiovascular disease the way we do mental illness, we’d prescribe a heart attack patient aspirin for the pain rather than address the underlying heart disease. In other words, we’d risk doing more harm than good.

We have no drugs that eradicate mental illness, but we keep acting as if we do.

While over-medication is an important challenge, we also shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. The Medicalization mindset, however, makes it hard to see this.

For example, Tough describes a major longitudinal study, the MTA study, as proof of medication’s failure - and a reason to reframe A.D.H.D. as a difference rather than a disorder. In the study, researchers assessed the long-term effects of Ritalin on A.D.H.D. symptoms. After being treated with Ritalin for 14 months, children in the active group (versus control groups) showed greater improvements in symptoms. By 36 months, however, the benefits had disappeared. Tough frames this as a failure of medication.

This doesn’t look like failure to me. This looks like exactly what you would expect. Stimulants such as Ritalin only boost focus and motivation as long as they’re taken. Once the treatment stopped in the MTA study, the benefits would almost surely have disappeared quickly, too - unless medication had been combined with non-medication therapy.

Add to this that if you dig in on what happened in the MTA study between the intervention ending (at 14 months) and the follow-up (at 36 months), it was the Wild West. Kids in both the active and control groups pursued a mishmash of medication/therapy/self-help/nothing. Any effects of medication, even if they lingered, would have been drowned out in the noise of people just doing whatever they could to feel and do better.

False Dichotomy #3: A.D.H.D. either has concrete biomarkers or it is not a disorder

Medicalization tells us that for a disorder to be a disorder, it must have clear biological identifiers, or biomarkers. Here, A.D.H.D. doesn’t pass muster. While some studies document small biological differences between those with and without an A.D.H.D. diagnosis, there are no brain scans or genetic markers for A.D.H.D. yet, no blood tests that tell us, “You have it or you don’t.” Medicalization leads us to believe that the reality of A.D.H.D. as a disease depends on these things.

Indeed, it’s hard to shake this idea that “real A.D.H.D.” must be “biological A.D.H.D.” since it’s defined as a neurodevelopmental disorder - appearing early in development (before age 12), often emerging when environment demands change (e.g., school starts) and the child’s capacity to adjust to these demands is inadequate.

In a recent NPR interview, Tough said about a 2002 international consensus statement spearheaded by Barkley and signed by 85 A.D.H.D. researchers, “What I was drawn to in that statement was the focus on biomarkers, on particular biological signatures that could let us identify A.D.H.D. and in the process say, this is clearly a biological condition, not just a psychological one.”

But this is just another Medicalization red herring. Biomarkers for mental illness are virtually non-existent. There are none for anxiety, depression, addiction, bipolar disorder, personality disorders, PTSD, and the list goes on and on. There’s no one biological litmus test for any of these disorders. That doesn’t mean that any of these mental illnesses are “just psychological.” Instead, it means they conform to a first principle in Psychology - the diathesis-stress model of mental illness.

This model posits that mental illness emerges from a combination of hereditary dispositions that confer risk (diathesis) and experiences of challenge or adversity (stress). These risk factors aren’t fate. But when they interact with certain stressors or a poor environmental fit - everything from exposure to toxins to difficult social experiences to trauma - they can trigger mental illness. This idea helps explain why two people can experience the same trauma - war, natural disaster, violence - and only the person with a certain diathesis develops PTSD. Psychological researchers conceive of A.D.H.D. in this way, too, and have long acknowledged and studied phenotypic variability and the spectrum of distress and dysfunction. That’s how diathesis-stress works - it’s both unique and universal.

Because of the Medicalization mindset, however, we have spent an inordinate amount of time looking for a universal biomarker for A.D.H.D. We even have some great candidates - like immature executive function, emotion regulation deficits, and difficulty tracking temporal delays. But we’ve resolutely failed to find “the one.” But why should we expect there to be “the one?” The diathesis-stress model tells us, “It’s complicated” and there’s rarely a single cause - or even just a few.

These risk factors aren’t fate. But when they interact with certain stressors or a poor environmental fit - everything from exposure to toxins to difficult social experiences to trauma - they can trigger mental illness.

Because of this biomarker uncertainty, however, Tough goes on to wonder whether A.D.H.D. is better conceived as, “...a misalignment between their own unique brain and the situation that they're in. And if that's the case, sometimes medication can still help make that environment more tolerable. But there also might be things that we could change in their environment, that they could change in their habits and patterns that would have the same kind of positive result that medication would have.”

I think this is a good argument for putting needed brakes on medicating children. But it doesn’t mean that we should downgrade A.D.H.D. to a personality difference or a brain-world misalignment. Nor should we think of those diagnosed with A.D.H.D. as having a broken brain that needs to be fixed with medication.

And here’s the kicker about the debate – neither Tough nor Barkley would take either of these two extreme positions. But somehow, each of them seemed to believe the other would.

Medicalization, and its inherent false dichotomies about mental illness, make it hard to see anything but the binary. It makes it hard to see that we can flexibly and mindfully use medication and make environmental adaptations. Medicalization makes it hard to see that if we focus too much on risks, deficits, and stresses, we risk ignoring how we can build strengths and positive capacities. It makes people desperate for a diagnosis, even when it’s the wrong answer to the right question.

The Alternative: Slow Mental Healthcare

“When we are suffering, it feels natural to seek a diagnosis. We want a clear label, understanding, and, of course, treatment. But is diagnosis an unqualified good thing? Could it sometimes even make us worse instead of better?”

~The Age of Diagnosis, Dr. Suzanne O’Sullivan

Pushing back against the either/or thinking endemic to Medicalization, we see that the A.D.H.D. dichotomies break down, leaving us with new ideas:

A.D.H.D. doesn’t fall into clean categories, but it’s still a real disorder.

Medication can help reduce A.D.H.D. symptoms, but even if it doesn’t, it’s still a real disorder.

A.D.H.D. doesn’t have universal biomarkers, but it’s still a real disorder.

Breaking these dichotomies frees us from equating A.D.H.D. with a “broken brain” and reflexively medicating. It also frees us from assuming that A.D.H.D. is just a personality difference, or that “medication is bad” and so we shouldn’t even consider it.

Once these assumptions are slowed down, we - families, schools, doctors, and of course patients - can better decide whether a diagnosis is helpful, whether a prescription should be tried, how environments can be adapted, and how to amplify a person’s strengths while their difficulties are supported.

I think of this as Slow Mental Health. Like the Slow Food movement - an alternative to fast food that promotes local, regional, and non-processed food - Slow Mental Health would normalize taking more time to do careful assessment for non-urgent mental distress rather than incentivize fast diagnosis and medicating. It would allow time for healthcare professionals to evaluate how a diagnosis would or would not be beneficial to the individual in front of them.

In her excellent and controversial book, The Age of Diagnosis, Dr. Suzanne O’Sullivan points out that diagnoses are useful, but only if they lead to better outcomes for patients. This happens when the diagnosis correctly identifies a problem that can be matched to an effective, available treatment.

When, how, and for whom is the diagnosis of A.D.H.D. leading to better outcomes? We’re in such a rush to diagnose and treat, assuming that more of both are always better, that we never stop to find out. Sometimes, like for my student Rick, it’s a mixed bag - self-acceptance and support from the neurodiversity community were positives, but performance and emotional wellbeing weren’t yet heading in the right direction. Did the disorder label make him doubt that change was really possible even as it boosted his self-acceptance?

Sometimes, diagnosing and biologizing are the last things people need to get better.

Take the nocebo effect - the opposite of the placebo effect, where believing that you have a disorder leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy and loss of faith in one's autonomy and ability to heal. Biologizing A.D.H.D., especially on the mild end of the spectrum, can convince people that they have no control over their problems, even when they might. They start to give up on change and lower their expectations for happiness. Here, labelling might even create an illness identity, in which being sick is integral to one's very sense of self, at the cost of developing a recovery identity. Chronic illness identity predicts worse health outcomes.

When, how, and for whom is the diagnosis of A.D.H.D. leading to better outcomes? We’re in such a rush to diagnose and treat, assuming that more of both are always better, that we never stop to find out.

Tough interviewed leading A.D.H.D. researcher Edmund Sonuga-Barke, who himself has been diagnosed with A.D.H.D. Sonuga-Barke believes that the emphasis we’ve put on biological aspects of A.D.H.D. has outweighed more important factors - people’s experiences of self-hatred, failure, and problems coping with emotions. He argues that our focus on deficits in A.D.H.D. is at the expense of bootstrapping individual strengths and capabilities. Less money for drug research and more for making schools supportive places for A.D.H.D. and learning differences? Money well spent.

Even with his doubts, however, Sonuga-Barke never argues that A.D.H.D. isn’t a medical condition or that medication shouldn’t be used. He’s simply saying that it’s not all biology, and there’s no medication magic bullet. Most psychologists - Russell Barkley included - would enthusiastically agree with this message. Our Medicalization mindset, and the false dichotomies it creates, blocks us from having these commonsense conversations.

Psychology is a medical science - and has yielded immense benefits as a result. But these benefits can be negated when we adhere to unexamined Medicalization. What does a different approach look like in the context of A.D.H.D.?

Stop talking about A.D.H.D. as either biological or psychological.

Understand that medication doesn’t “fix” A.D.H.D. - but it might help manage symptoms.

Use medications cautiously because they have side effects. Combine them with non-medication therapies to promote lasting benefits.

Acknowledge that A.D.H.D. is a disorder on a spectrum. Do more work to understand the unique needs of people on different points of the spectrum, and design interventions accordingly.

Understand individual differences as symptoms only if they directly cause impairment.

Consider not giving a diagnosis if it doesn’t lead to meaningful and helpful treatment.

Focus therapy on building strengths just as much as on remediating weaknesses.

These principles are already possible - and exist - in our current system. But they’re drowned out by the black-and-white pronouncements of Medicalization and the monetary incentives that keep the system going. Our fundamental first step must be to slow down and rethink our ideas about A.D.H.D. If we do and stop trying to shove square pegs of psychological struggle into the round hole of Medicalization, we will make better choices for ourselves, our families, our patients, and our communities.

Not his real name, and some details modified to protect privacy.

A thoughtful and interested analysis. I'm a pediatrician/prescriber in the US. I've seen all types of ADHD and offered support for families for nearly 20 years -- and I'm still not sure if I'm doing it right! Especially with younger kids, the brain and environment are so drastically changing from year to year, treatment plans require flexibility and routine evaluation. I've seen kids' lives change with ADHD meds, but I also know that meds aren't a 'set-it-and-forget-it" solution. As kids grow and learn how their brain and body work, I find many (not all!) can decrease or remove medication support over time.

Such a great perspective! Appreciate all of that. I keep wondering what the data will look like for changes that happened during and post pandemic. Seems like there are so many more people being diagnosed or self diagnosing ADD and/or suffering from greater anxiety and feeling that their world and the people they encounter are “not safe”. The isolation played a role too. Think it would be so helpful for people to learn how important it really is to build back their resiliency muscles aside from medication options.