Why We Should Ditch Digital Absolutism

Digital absolutism will fail to deliver in the end. We need digital citizens, not purists.

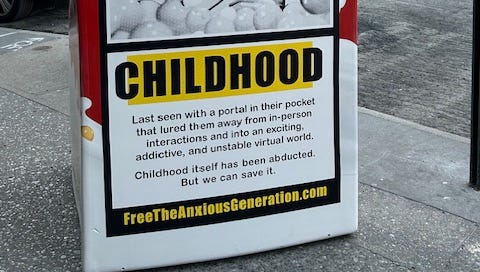

As I turned the corner by the NYC Union Square Barnes & Noble, I ran smack-dab into a giant milk carton:

This was one of several installation art-like advertisements pleading with passersby to free the anxious generation from the tyranny of smartphones. They took up half the sidewalk. They were promoting the new book by

, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Caused an Epidemic of Mental Illness. The personable young man handing out flyers proudly told me that they’d sold out Barnes & Noble. Mission accomplished.But to be fair, as I wrote in my review of the book for the New York Times, Haidt is a man truly on a mission - and that mission is to roll back the ubiquity of smartphones in childhood. His timing is perfect, because we’ve - finally - collectively come to the same conclusion: spending huge portions of our lives on screens simply isn’t good for us - especially our kids. This should have been obvious, of course, but our obsession with the Silicon Valley wunderkinds - so impressive (and rich!) and promising to make our lives more connected and meaningful - blinded us.

But here we are now, and we all feel what Haidt uses data to convince us of: Big Tech will disrupt anything, including our humanity and well-being, to increase their profit margin. They will downgrade our lives by keeping us hooked on screens longer with each new (planned-obsolescence) upgrade if it squeezes just one more dollar out of us.

Few readers will need me to explain our moment of tech backlash, so perfectly encapsulated by

in his description of SXSW cool kids booing at a video boasting about the wonders of AI. You probably feel it yourself. You also don’t need me to explain how the attention economy or surveillance economy work, or that smartphones and social media are addictive by design and perpetually distracting.But having said all that, and having written about and researched the negative impacts of technology on our wellbeing, it still doesn’t mean that digital technology has caused the youth mental health crisis.

That’s the Ideas Industry, to borrow a phrase from Daniel Drezner’s new eponymous book, talking. Because it’s easy to sell a single cause rather than to take a hard look at complexity. Or to ask - what happens when the all phones are taken away? Will our kids be healed? If only it were so (I have other ideas about what’s driving us into the arms of these devices, but more on that later).

That’s why Haidt’s, and other digital absolutists’ interpretation of research is contentious. As I wrote in the book review:

Few would disagree that unhealthy use of social media contributes to psychological problems, or that parenting plays a role. But mental illness is complex: a multi-determined synergy between risk and resilience. Clinical scientists don’t look for magic-bullet explanations. They seek to understand how, for whom, and in what contexts psychological problems and resilience emerge.

Online—but not in the book—he reports that adolescent girls from “wealthy, individualistic, and secular nations” who are “less tightly bound into strong communities” are accounting for much of the crisis. So perhaps smartphones alone haven’t destroyed an entire generation. And maybe context matters.

And perhaps most importantly, when it comes to public health, absolutism just doesn’t work.

Nancy Reagan’s Just Say No drug campaign? A public health case study in what not to do. During the AIDS crisis, fear mongering and abstinence demands contributed to more unsafe sex. Remember the pandemic? Telling Americans to wear masks at all times undermined public health officials’ ability to convince them to wear masks when it really mattered.

Absolutism can also exact opportunity costs, blinding us to valuable solutions.

In 1960s Britain, annual suicide rates plummeted. Many believed it was due to improved antidepressant medications or life just getting better. They weren’t looking in the right place. The phase-out of coal-based gas for household stoves blocked the most common method of suicide: gas poisoning. Means restriction, because it gives the despairing one less opportunity for self harm, has since become a key strategy for suicide prevention.

I don’t know about you, but when I was a kid (I’m a Gen Xer), there was no shortage of mental health struggles. You can argue about whether there are higher rates of youth mental illness today compared to those supposed halcyon days - diagnoses, measures, and self-report biases change radically over time, which could in part explain the report of higher rates today. Regardless, no one ever has found that mental illness is a simple one-to-one relationship between something bad in the world and the human being’s capacity to adapt well or poorly.

Do I think we need to get our digital lives in order? Yes. Do I think we ALL - not just kids - need less time on screens? Yes. Also, as a clinical and developmental psychologist, I have studied and written about child resilience and the need to promote youth antifragility, an important and honestly more scientifically defensible point of Haidt’s book.

But I believe even more strongly that digital absolutism carries unacceptable costs: obscuring other sources of risk, failing to interrogate why the majority of youth are not negatively impacted by digital tech, and blocking opportunities for youth to build effective skills with technologies that are going to be around for a long time. He advises that kids shouldn’t get access to social media before college. How about fostering a healthy relationship with tech so that once they’re out of the family home, digital binging doesn’t become as common as alcohol binging on college campuses? Unfortunately, absolutists don’t believe that’s possible. Chastity pledges are better than sex education, after all.

In the launch of his book promotion on GMA, which to be fair a terrible place to get complex ideas across, Haidt says, “When kids moved their social lives onto social media, it’s not human, it doesn’t help them develop, and right away, their mental health collapses.” Dude. It just doesn’t work that way. You know that. But he also believes, as he wrote in his book, “The phone-based life produces spiritual degradation, not just in adolescents but in all of us.”

Personally, I agree that digital life is degraded, meaning inferior, to IRL for a million reasons. I appreciate that a scientist like Haidt would bring his consideration of the spiritual to his book. I feel what he’s saying about that kind of degradation as well. But creating a moral dialectic of good versus evil when claiming to just interpret the scientific data is a misdirect, and it’s not the way of science. It’s the way of propaganda or advertising.

I truly wish the digital absolutists well in their mission to reduce humanity’s screen time in favor of IRL. I hope the upside of this black and white thinking is that policy makers change laws and increase regulation. I hope parents who need to look up from their own screens do so and pay attention to the digital lives of their kids. But you don’t need absolutism to elevate human connection over digital. Digital absolutism, like all binary approaches to life, will distort the truth and fail to deliver in the end. We need digital citizens, not purists.